Why Is Debt So High?

Low Growth

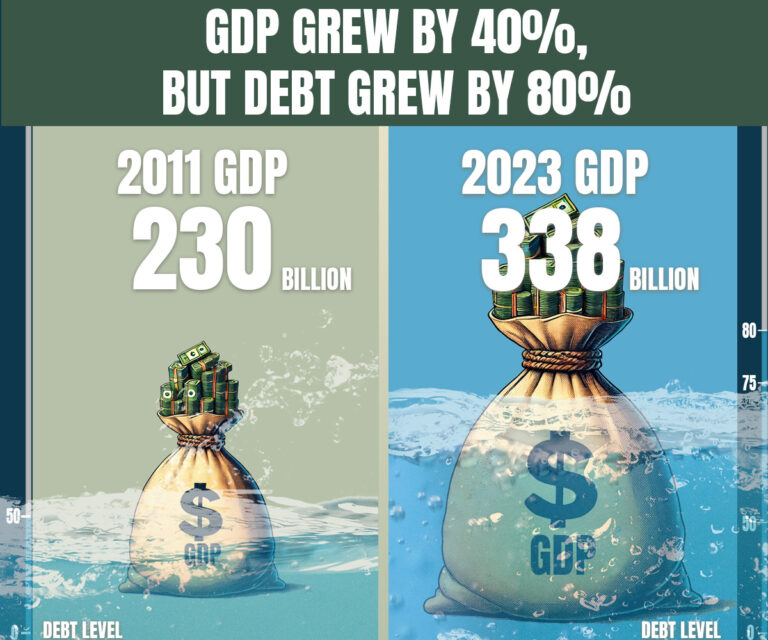

Pakistan’s economy is not generating enough income to pay for the rise in debt servicing payments. Whilst its economy has grown by 40 percent since 2010, its total debt has doubled, i.e., debt growth outpaces income growth by 2.5 times over an extended period of time.

Economic growth and debt growth by decade 1960-2024

Pakistan’s economy is not generating enough income to pay for the rise in debt servicing payments. Whilst its economy has grown by 40 percent since 2010, its total debt has doubled, i.e., debt growth outpaces income growth by 2.5 times over an extended period of time.

In the 1960s, Pakistan was a fast-growing, dynamic economy that was taking on debts to build dams, steel mills, and electricity distribution networks—productive, growth-enhancing investments. However, as the focus shifted to security and wars, and more recently in managing climate crises, debt is being used in non-productive sectors, which inhibits long-term growth.

Low Tax Revenue

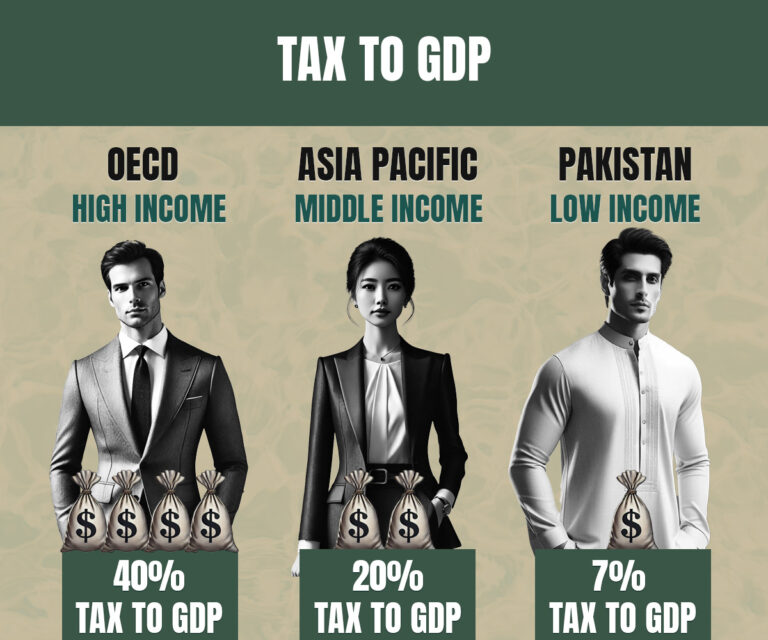

Pakistan raises too little tax from its people. A 2024 WorldBank report suggested that “there is a tax threshold around 15 percent of GDP where future inclusive growth significantly improves”. Compared to developed countries like OECD where over tax collection is a third of GDP, and Asian-Pacific countries which raise around a fifth, Pakistan’s tax-to-GDP ratio ranged below 11 percent in the last fifteen years.

Another way to see this comparison is that this is two-thirds of the median tax-to-GDP ratio for even developing countries, which is 16 percent.

Figure 7: Tax-to-GDP ratio

Even though it has a high tax rate, Pakistan collects taxes from too few people and organisations. Rampant tax evasion and avoidance is built on a weak tax administrative system. Hence, instead of spending from revenue, Pakistan finances its expenses with debt.

High spending on defence

Pakistan’s short history is riddled with regional conflicts. As a result, the country maintains one of the largest armies—fifth globally, in terms of personnel.

Almost a fifth of Pakistan’s budget expenditure goes directly to defense. This does not include indirect expenditures on pensions (estimated at another 4 percent of the budget expense) and national resources directed towards maintaining a large military-industrial complex and the military businesses and investments (estimated in 2017 to be USD 20bn or 13 percent of GDP).

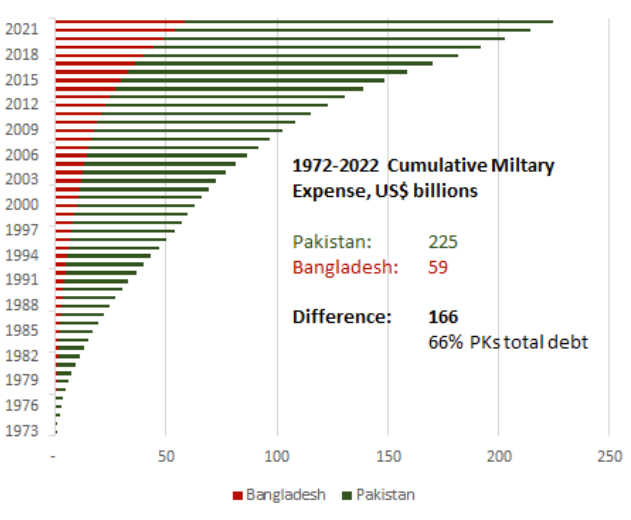

Pakistan versus Bangladesh cumulative military expense since 1971

One way to understand the scale of such long- term lop sided priorities is to compare what others have done. Consider this: compared to Bangladesh which separated from within Pakistan in 1971, between 1971 and 2022, Pakistan has spent nearly USD 166bn more than its twin even though the size of their economies is comparable i.e this is same as the entire domestic debt of the country.

Pakistan suffers from chronically low exports. In 2023, Pakistan’s exports were USD 35bn compared to USD 60bn in imports. Since 2000, Pakistan’s exports have grown at less than 11.6% per annum while imports have grown by 100%.

In the same vein, Pakistan has struggled to attract foreign direct investment. Pakistan ranks 81st on the global net FDI inflow list.

While economies like India, Bangladesh and Vietnam have grown their dollar reserves on the back of export and FDI growth, Pakistan’s State Bank is constantly going to the IMF for emergency lending to fill the currency reserves required to meet their external debt servicing amounts.

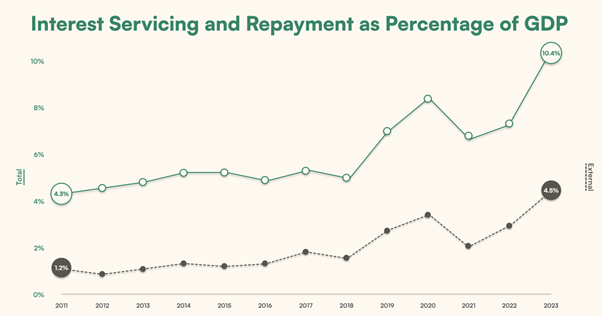

What it costs?

No Fiscal Space

The higher cost of borrowing, especially for external loans, has compounded the problem, making it increasingly difficult for Pakistan to escape the debt cycle.

As a result of these heavy debt servicing payments, the government has less fiscal space to spend on development and social services.

No money for social uplift

Currently, Pakistan spends only 2.5% of its GDP on education and 1.1% on healthcare, which is far below what’s needed for a country with such a large population. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended level for the percentage of GDP spent on health is 5%.

One of the biggest consequences is on children’s health and development. Around 40% of children in Pakistan are stunted, which means they won’t reach their full physical and mental potential. This is partly because of poor investment in healthcare and education, which limits their ability to grow and develop. This isn’t just a health issue—it’s an economic one. When we underinvest in our people, we’re setting up future generations for failure.

Another impact is on income inequality. While the rich are getting richer, the poor are left struggling. The government’s focus on paying back debt means less money is available for programs that could help reduce poverty or create jobs.

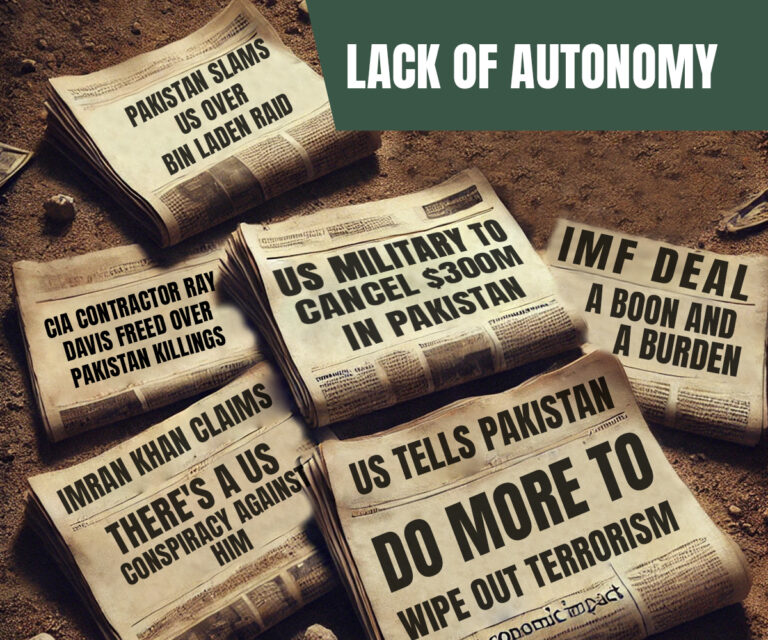

This also makes Pakistan vulnerable to external shocks. Every time there’s a global crisis, like a recession or a rise in oil prices, Pakistan’s economy takes a hit. This forces the government to turn to the IMF for help, but these loans often come with tough conditions that cost Pakistan its autonomy. To date, Pakistan has been bailed out by the IMF 23 times, the most of any country.

Being in a position where you are in debt and frequently risking default also damages Pakistan’s reputation and credit ranking internationally, which affects Pakistan’s ability to borrow money in the future.

What Can We Do?

Although Pakistan’s debt situation seems daunting, there are solutions.

The first thing to do is to increase the awareness of the problem. This website is an attempt to do just that. Debt is slowly becoming an existential crisis for the Pakistani economy but the voters do not even mention it as a top item of concern. Whilst comings and goings of IMF teams are discussed daily in TV shows, the conversation is far too detached for the general population and students to gain any insights. Debt and Pakistan’s economy have to become serious topics of conversation.

In terms of policy, the government needs to increase its tax revenue. Currently, only a small portion of people and businesses pay taxes. The tax man never enters large swathes of the country as agriculture and trade is not taxed in Pakistan in 2024. If Pakistan can raise its tax-to-GDP ratio to the 16% rate of the median developing country, it could generate PKR 13tn (USD 4bn) -, enough to take away any need to borrow more and still have extra funds for social uplift and development.

In the immediate term, Pakistan needs to start offloading all loss-making state-owned enterprises like the PIA, the national airline, which loses over PKR 200m daily by some estimates. Once seen as beacons of progress in the late 20th century, these SOEs required PKR 905 billion of taxpayer monies in 2022-23 just to stay afloat. Successive governments have delayed the privatization process of these companies due to political expediency. This was proven in the failed attempt to privatise PIA in late 2024. However, with such companies’ current trajectories, this process is no longer affordable.

The Pakistan state needs to re-tune the economy towards modern methods of attracting capital and investment, which currently averages at a paltry one billion dollars annually. Pakistan’s economy seems to offer minimal incentive for investment, from the ease of doing business, where Pakistan ranks outside the Top 100 economies, to the regulatory systems or judicial remedies. While this is not possible to achieve in the short run, almost every emerging economy which graduated to developed status in the last fifty years has done so on the back of healthy foreign direct investment.

In the long run, diversifying the economy and improving value addition is the only hope for sustained growth in Pakistan. Right now, in terms of exportsimports, the rest of the world only needs Pakistan for agricultural produce and textiles, which don’t offer much growth in terms of value addition. Essentially, Pakistan needs to start producing things that the rest of the world wants and it needs to do it in a high-productivity environment. Pakistan can only do so if it begins to exploit its benefits: educate its large, young population in modern sciences, start trading in its own region – it is disconnected from India in its east and Iran in the west, and develop its indigenous resources like minerals and renewable energy.